Got Potato Milk? New Plant-Based Option Is More Sustainable, Too

Sweden's Dug eyes a bigger consumer market

Almond. Cashew. Coconut. Rice. Soy. Hemp. Oat. Pea. Potato? Each are plant-based milk options. So, what’s potato doing there?

It’s the newest plant-based milk on the scene and hopes to surpass more well-known options like almond, coconut and oat milk. Potato milk is more sustainable, allergen-free and has less sugar than its competition. But the average consumer needs to be educated on the benefits of potato milk and why it should replace their already beloved plant-based option.

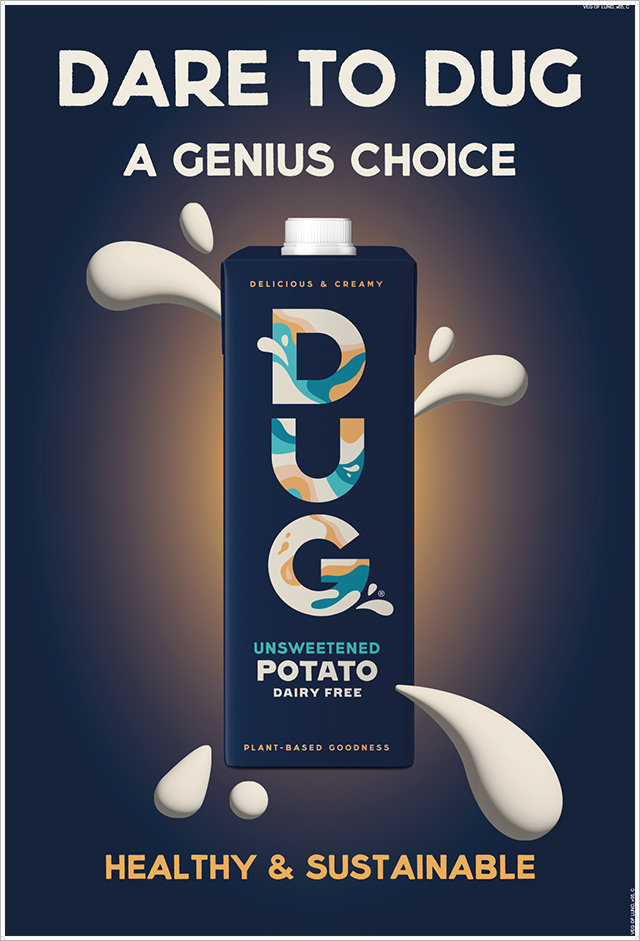

Dug is up for the challenge. The potato milk brand, owned by Veg of Lund, was discovered in Sweden and comes in three flavors: original, barista and unsweetened. It’s currently sold in Europe online at Amazon, Navesu, Ocado and The Vegan Kind and online and in-store at Waitrose. One liter containers cost anywhere from £1.30 to £2.39. A variety pack of all three flavors costs £7.50, and a six-pack of all one flavor is £12.50. The company is also experimenting with a 10-liter bag-in-a-box option for use in industrial cooking settings.

The brand won Best Allergy Friendly Product at the 2021 World Food Innovation Awards and came in second place as best plant-based beverage.

For our On Brand series, we spoke with professor emerita Eva Tornberg, head of product development and innovation at Veg of Lund, about potato milk’s sustainability compared versus almond milk, happy accidents, and breaking into the U.S. market.

Discovering potato milk was unintentional. Tornberg was working on a research project on potato proteins to determine how well they worked as emulsifiers. Animal proteins found in milk and meat are traditionally better emulsifiers than vegetable proteins. As her research continued, Tornberg realized potato proteins had some amino acid composition that’s similar to milk and eggs. It’s also allergen-free and makes foam.

“It struck me. Why has no one worked on root foods?” says Tornberg. “Most people work on cereals. Everyone is so focused on oats and so on. I thought, ‘Why couldn’t we use potato?’ “

Veg of Lund’s first product was My Foodie, a set of three smoothie drinks that combined potato, rapeseed oil and apple with raspberry, sea buckthorn and blueberry for drinks high in omega-3.

Dug also uses the potato and rapeseed oil combination, adding pea protein and other allergen-free ingredients.

“The barista is meant for coffee and it can foam and make cafe lattes,” says Tornberg. “Original can be used for cornflakes, and I think it’s good for baking and to use in cooking because this potato milk has no strong taste, no strong off-taste. It’s rather neutral.”

When researching potato milk, Tornberg’s main focus was its nutritional value, but the deeper the dive, the more sustainability moved to the forefront.

“I started studying nutritional properties of the protein,” Tornberg tells Muse. “But then I started to realize how sustainable it is because, when you cultivate potatoes, you can have a yield of 40-60 tons per hectare, and for oats you have 4 tons per hectare. Oats have a higher dry matter [what’s left of a grain after water is removed], but you can’t use all dry matter with oats. You have a lot of byproduct. We use the whole potato, so we don’t have any byproducts. We take off the shell, of course, but there’s pretty much no waste.”

The amount of water conserved to make potato milk versus almond milk is staggering. Tornberg notes that it takes “16,000 liters of water to make one kilo of almonds and 287 liters to make one kilo of potatoes. It’s such a difference. Almond milk is cultivated in very warm places like California, where you have a lack of water, so…”

Potato milk is comparable in calories to other plant-based milks; sugar is where the differences lie.

“We have a little bit more starch than others, but we have 3 percent sugar. Oatly has 4 percent, and milk has 5 percent,” says Tornberg. “Oatly doesn’t have an unsweetened option because it’s very much dry matter, so they have to solubilize it with enzymes. We don’t have to do that. During that process, a lot of sugar is formed. You can’t take away the sugar. We are just adding sugar and have one without sugar if you want that, too.”

With three potato milk flavors on the market, Dug is looking at ways to branch out in the plant-based milk, frozen desserts and alternative meat categories.

“It’s always another flavor,” Tornberg says. “Chocolate and so on. Everyone has it. But we are also looking into ice cream now. And it looks very promising. We are also doing a cream and we are now working with alternative meat. It’s always a base of potato and a little bit of rapeseed oil and we work with the potato and pea protein.”

With the plant-based milk category becoming more saturated by the day, Dug recognizes the challenge to educate consumers about potato milk and switching to it in lieu of the plant milk already in their refrigerators.

The brand is daring consumers to try their product with a “Dare to Chase Taste” print and OOH campaign, running in Sweden and the U.K. In one ad, a man pours Dug all over his face and body (think the Flashdance scene, using milk) with copy daring consumers to try “Creamy. Sustainable. Potato milk.”

Click the images to enlarge and scroll through:

Three additional ads, one for each flavor, have varying copy, ranging from “Dare to Dug. Go potato” and “Go potato. It’s Dugelicios” to “Dare to Dug. A genius choice.”

“When you work in the consumer market with new products, it’s always difficult,” notes Tornberg. “It demands so much marketing. But I think what we really have is the sustainability, which I think, really, no one else has.”

Dug also has a partnership with WW (formerly Weight Watchers) in the U.K., where a variety pack of Dug is offered as a reward in the company’s WellnessWins program.

Potatoes may be inexpensive, but making potato milk is pricey until Dug sets up production facilities in the countries they want to sell it.

“When you start a production, it’s always more costly at the beginning because you don’t have the large quantities,” concludes Tornberg. “But when you make larger quantities, it will go down. I think there are prerequisites because potatoes are not that expensive. But at the moment we can’t make it so cheap because we’re making it in England. We have the production unit in England, and then you have to transport it. We want to have the production in the same country as we sell it.”

Events

Events