Inside the Art of Agnes Arellano, Sculptor of the Sacred Feminine

Carving divine rhyme into patriarchal reason

For a certain kind of kid, mythology is the best part of history class. The exploits of immortals—icons of beauty, wisdom, war and craftsmanship, but also deception, cunning and not a few kidnappings—are the stuff of epics.

It’s hard to remember that, once, these weren’t just stories; they were religion. The exploits of Greek, Roman and Egyptian gods were lessons—not just in behavior but also guidelines for understanding who you’re dealing with.

Want to get pregnant? Ask Hera, Greek goddess of women and childbirth. Just be careful when you call; Zeus might be listening, and he’s kinda got a reputation.

Philippine artist Agnes Arellano has a body of work that goes back to the early 1980s. It’s not only deeply mythological but profoundly, even subversively feminine, sometimes in ways that are dark and terrifying—this in a country dominated by monotheistic religion and a political strongman, who’s as much a feminist as he is subtle.

Her work has been exhibited in Berlin, Fukuoka, Havana, Johannesburg, New York, Brisbane and Singapore. She also founded the Pinaglabanan Galleries in San Juan, Metro Manila—a tribute to her late father, mother and sister, who died in a fire in 1981. The Galleries—which became a space for intercultural exchange and discovery—were built on the fire’s ruins.

Unsurprisingly, Arellano’s work is deeply psychological, exploring love and pain, the physical and spiritual, what we consider sacred and why.

Her current work in progress, Project Pleiades, is inspired by the Greek tale of the Pleiads, the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas and the oceanid Pleione. The nymphs formed part of the train of Artemis, goddess of the hunt and of the moon, and helped nurse and train an infant Bacchus.

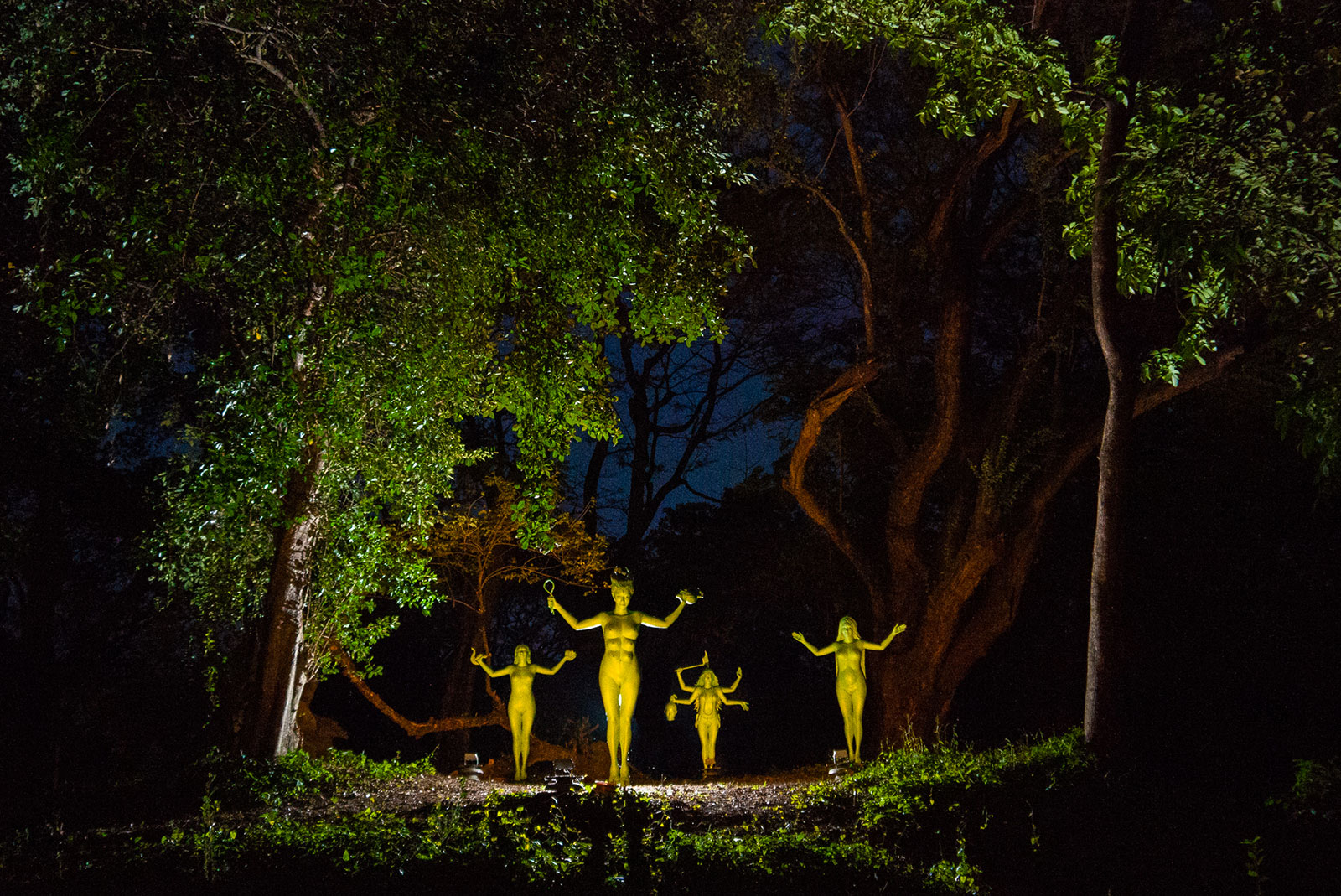

Instead of sculpting the sisters themselves, Arellano is recasting them as seven goddesses from different pantheons. The four goddesses made so far are unapologetically powerful—and in some cases ferocious, practically obliging the viewer to pause and offer homage.

Mythology, we remember, is the stuff of worship. And worship is as often an act of fear as of love or awe.

The deities of Project Pleiades “are based on ancient religions and myths, and [are] part of my lifelong research on the feminine principle in religion, a search for the Sacred Feminine,” Arellano writes on her website. “Using body casts of my own naked body to delve into comparative mythology and archetypal symbols, I depict four goddesses with their arms in the epiphany position.”

This new pantheon was first exhibited in 2016 for Art Fair Philippines, tea-stained and somber. They’ve since been given an upgrade; the image that appears above is from 2018, part of a grove installation titled “Project Pleiades 2” for an exhibit called “Lawas.”

In an interview with Muse, Arellano talks about Project Pleiades, the Philippine moon goddess Haliya, and her creative approach. Check it out below.

Muse: Explain Project Pleiades. What’s its origin story?

Agnes Arellano: It began with Haliya, the Moon Goddess of Bicol [Philippine] myth, the central figure in my first inscape, Temple to the Moon Goddess in 1983. Since then it has been the continuing saga of a Search for the Sacred Feminine.

Feeling rejected by the Catholic Church, I sought refuge in an alternative Deity, one more forgiving, benevolent, caring, gentle and understanding than the all-righteous One, who exacts punishment and threatens hellfire.

In mythology, Haliya and her six sisters came down periodically to bathe in the warm waters of Earth (an ancient explanation for menstruation). She got stranded, was wooed and won—even betrayed!—by an earthling woodsman who had hidden her clothes, her vehicle to and from the Moon.

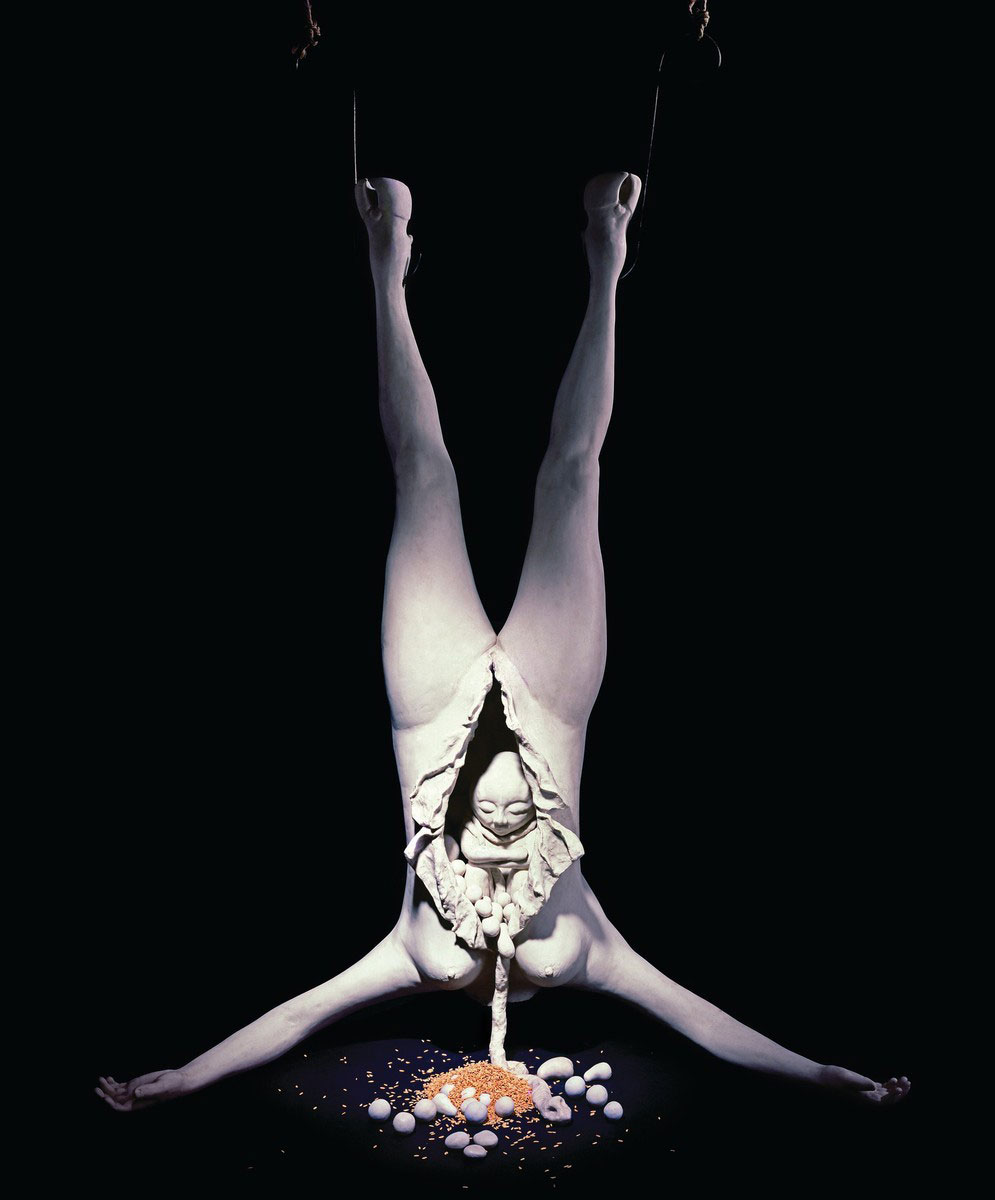

[In Temple to the Moon Goddess], the floor piece is a pregnant woman with legs splayed out in the moment of childbirth: Haliya in her no-longer-immortal guise is back bathing in the Sacred Spring, wondering about the fate that will befall the demigod inside Her.

So Haliya is one of seven sisters, like the Pleiades—four of which you’ve already recast as other goddesses…

Through comparative mythology, archeology, psychology and science fiction, I found four of the seven sisters in the star cluster Pleiades, the most visible star formation in our heavens next to Orion the Hunter, whose three-star belt my father taught me at an early age stood for [my sisters] Maria Lourdes, Maria Felicitas and me, Maria Agnes.

[In Project Pleiades], Haliya has morphed into Dakini, the female embodiment of enlightenment. She is also Tara. Her right hand holds a vajra for cutting away defilements and attachments that leave us in this unenlightened state. Her left hand holds a skull bowl, dispensing not “transgressive fluids” but instead “wisdom and blessings.” [The artist credits Ringo Bunoan of Mo Space with this colorful description.]

The myth of the sky dancer (also a description of Dakini) is fairly universal.

The three others are: the horned and hooved one, Inanna, my version of the multi-breasted Goddess of the Underworld from the Bagobo myth of Mebuyan (Mayauel in Mexico, Diana of Ephesus in Greece), who fed all the unborn children who died at childbirth.

Then from the bible came Mary Magdalene, my vindication of She who was maligned by the Church, excluded from the New Testament and rejected as a whore.

I cried angry tears conceiving this one, and here restore her to her place as the daughter of Isis, trained in the ancient mysteries of Egypt, the intellectual companion and most loved disciple of the Christ, whose fruit she bears in her rounded belly, and whose wounds she retains in her hands and feet.

Then, from the old Hindu world, Kali: Goddess of Time, Destruction and Death. In her upper right hand is a Kalinga axe for headhunting; in her opposite left hand is the mudra “Have no fear.” In her lower left hand is the mudra of generosity or boons, while the opposite right holds the head of the slain poet, one of the many victims in her fury towards the monsters who would destroy the world, for She is also the goddess who Ends destruction.

You’ve got three goddesses left. Who are they? Has the project changed since its start?

I do not know them yet; they have not manifested themselves. That’s how the process goes—with one’s being and becoming. Many of my figures are the result of the psychological processing I have subjected my real life experiences to.

In the myth of the Pleiades, the seven sisters all have the same face. That is why I cast them all from one mold—my own face and body when I was much younger. Herstory goes that the daughter of Haliya would get her mother back if she could distinguish her from the others. Which of course she did, for that is how strong the umbilical cord connection—the psychic link between mother and child—is.

The nature of the project has not changed; they are still messengers, but the sisters have changed in appearance since the site-specific public art project “Lawas” (“Body”) was exhibited at the UP Diliman campus from April to August 2018.

They turned verdigris, to blend with the foliage in the grove where we chose to have them descend from the sky, their message being a return to Nature. As Joni Mitchell sang it: “We are stardust; we are golden. And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the Garden.”

The Philippines is dominated by three major monotheistic religions that revolve around a single male god. How did you become interested in its pre-colonial mythology?

Our pre-Hispanic beliefs and mythology survived the patriarchal religion imposed on us, mainly carried through folktales and the belief in the Mother Goddess through the Mother of Jesus.

I found my way there while searching for that alternative deity. Way before the colonizers obliterated our system of writing, we were etching poems on bamboo strips. Before we were called Maria or Juan [Spanish variants of Mary and Joseph], we had female priestesses—Babaylan—as well as the bulol: granary guardians, carved wooden icons that still stand in the rice fields and homes in the Cordilleras today.

A Tara statuette made of pure gold [found in the Philippines in 1918 but predating the year 1500] is testament that we had early exposure to Hinduism. We are said to be part of the mythical empire of Mu, and also have traces of the Chinese goddess of Mercy, Kwan Yin.

How did you find sculpting, or how did it find you?

Artmaking—painting especially—had always been there, coming from a long line of architects and artists, but an inclination for the Tactile versus the (flat) Visual came early.

As a kid I loved making doll brooches, little yarn people to the back of which I would attach a safety pin for pinning on to the lapel of our school uniform … or double-headed braided yarn heads for hanging on the car’s rearview mirror. I also made bunnies out of old school socks! I remember, as a young teenager, how annoyed I was when the boys started calling and interrupted this activity—doing things with my hands—which offered me happy oblivion.

I also had early exposure to “installation art,” I guess—the term was then unknown. My father put me in charge of laying out the family altar for the Christmas season. Alongside the manger, we had a tree lantern. The whole household would be busy after dinner, making tissue pompoms to attach to a chicken-wire cone with light inside. I remember asking the kids to design it one year, and we came up with black pompom outlines of stars, and Marvel comic-style graphics filled in with vivid colors.

In your Notebooks you say of your work, “We are not just talking here of fairy tales. The material has to plumb the psychological depths.” Can you elaborate?

My first university degree was in Psychology—clinical in particular. This journey to the Self has been long and tortuous, considering the many “Selves” we can occupy in a lifetime. Through myth and art, I processed my experiences, and like Siddhartha the prince, have come face to face with illness and death.

Or sometimes what we fight for isn’t always right, and we make so many regrettable mistakes acting out of pure passion. But then we recover, for as Tantra says, the greatest sin is passionlessness! Through all the narratives, conflicting and conflating, that I’ve woven together, I’ve discovered strands of archetypes, images from the collective unconscious that we as humans retained from primeval times. I use them like teaching models to help convey whatever I wish to express.

What is your greatest encouragement?

My father extricated me from my lackluster job as a psychometrician, carrying out surveys of how successful our training programs in the career foreign service were doing at the Development Academy of the Philippines.

Papa saw how uninspired I was, so he said I “could be his baby again”—that is, take a step back and do another course with his financial support. Before he passed, I took a mind- and life-altering trip—ironically a Roman Catholic pilgrimage—of holy sights in Europe, where I fell in love with Vincent in Amsterdam and Michelangelo in Florence, and was never the same again.

Who are you speaking to in your creations?

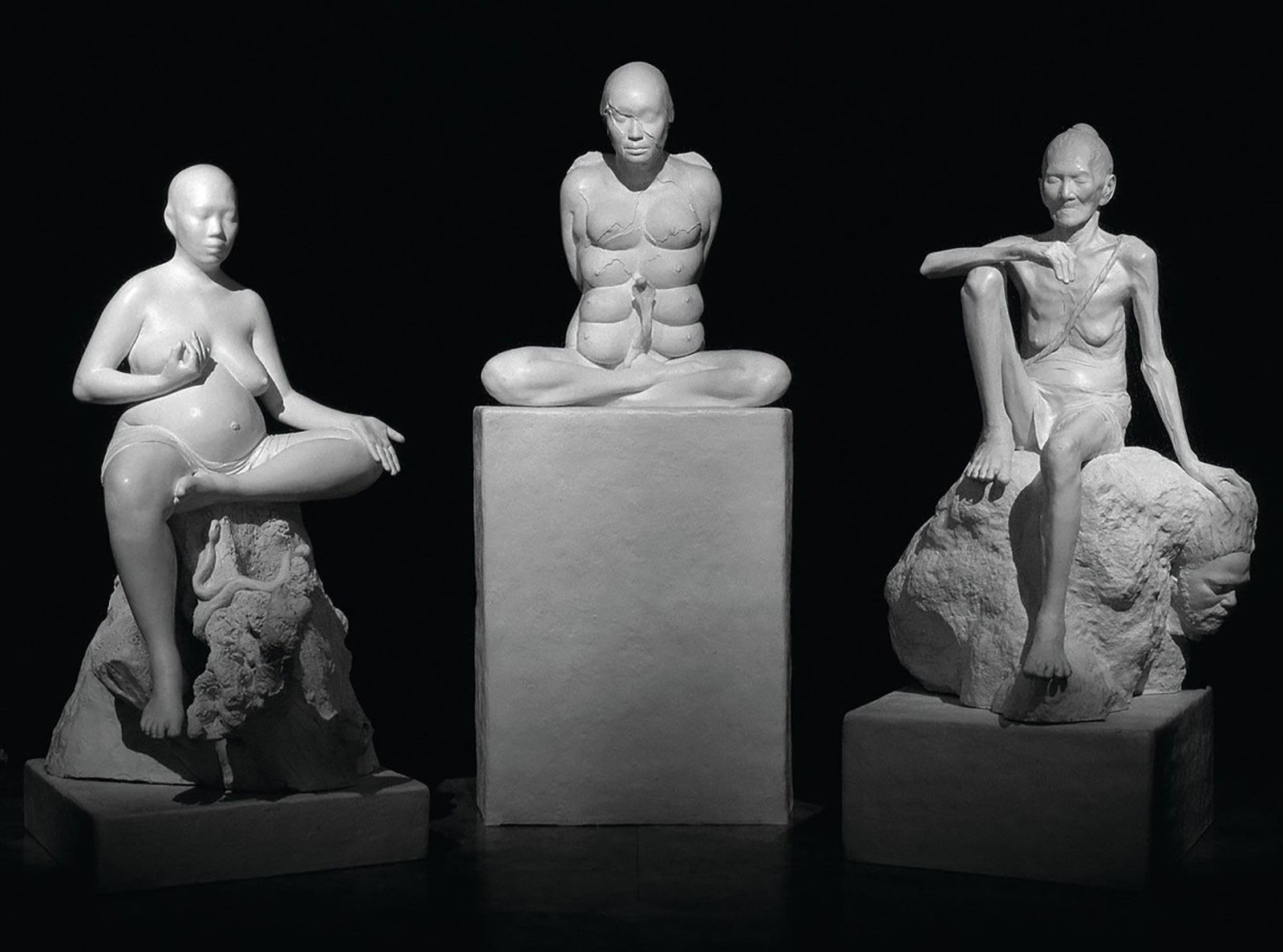

At one point onstage, speaking to an audience in New York during the exhibit “Traditions and Tensions” at the Asia Society, I found myself saying that I had noticed a “gaggle of geese” huddling about, showing interest in my Three Buddha Mothers. I realized then that although I was not consciously directing it to be so, I was speaking to the women. Or rather, was I speaking for them … ?

Let’s go back your early depiction of Bucol’s moon goddess Haliya, bathing in sand. Talk about your relationship with Haliya specifically.

Haliya was an expression of me, my dedication to a female deity which I projected to and embedded in my own body, a vicarious fulfillment of a dream to have a child of my own. It was prophetic. I could have sworn that the, her, my! body moved when I was laying her down on her crushed marble bed on the ground, and fixing her sights to the direction of the star Sirius B.

Since then, the same body has been used to portray other significant events in my life, like my painful cesarean delivery (Myths of Creation and Destruction), my midlife crisis (as Dea in Three Buddha Mothers), and other inscapes.

When did you start using your own body as a mold, and why?

From my very first inscape (the Moon Goddess temple), I used my own body as a mold. It began as a matter of convenience, a shortcut device much like photocopying, very easy to do since there was very little time to begin with. It eventually became the practice that blurred the difference between myth and reality, art and life.

Tell us what you’re most proud of.

In the sixth Havana Biennial, my Buddha mothers occupied a space in the old fortress. It was a dark old prison, with walls more than a foot thick and no windows, where the only occupant was an owl.

My assistant and I brushed and scratched away at the newly whitewashed walls to form dandruff-like “snow” on the floor, leaving an impression of the ruins of an old, long-abandoned temple. There was no electricity so I used coconut shell oil lamps, strategically poised on various parts of the sculptures, giving an eerie glow.

As the fort was still an active space—albeit mostly for tourists—young soldiers occasionally walked in to view the exhibit. I noticed that they stood there for what seemed like an inordinately long time, so I asked the curator what she thought it meant. She said, “Tienen miedo.” (“They are afraid.”)

This I was proud of, for I elicited a reaction I had hoped for: something like Awe… a sense of Fear in the face of the divine?

Another proud moment was seeing Haliya reproduced by Korean craftsmen in South Korea during the Busan Sculpture Biennial in 2006. They amusingly referred to my full-scale model as their “maquette,” and enlarged it—from a lifesize meter or so—to a length of four meters, carved from 15 tons of the lightest colored granite with pink specks.

I was happy, proud, but I didn’t feel like it was really mine anymore. I was thinking, as I sat on her huge belly, that my own hands could not have chiselled those smooth curves, nor could I have single-handedly created this grand monument to Nature in all her beauty.

What inspires a new project, and how do you take it from idea to reality?

Travel is a big key to new, mind-expanding concepts. My partner Billy and I have taken a number of pilgrimages to sacred sites around the world, just to taste the essence of the atmosphere in these temples. What constitutes a temple? What inspires awe?

In Bhutan, it was liberating to see that the image in the sanctum sanctorum is of two Buddha figures in coital embrace. After being so long in the shadow of a dead man hanging limply on the cross, this was a big opener—a very positive image of Creation, instead of Death and Sacrifice.

From this came Yabyum Yantra, an exhibit in synthetic onyx of seven couples in the yabyum (Tibetan father-mother) pose.

The male is always stoical while the female provides the movement. Thinking my body into positions where I would be staunchly anchored to the linggam while my feet danced was a meditative exercise in the least, where the vision dictated what the body should feel and how the image would achieve Form.

It was also in the steep mountains of Bhutan where the goddess gifted us with an apparition… and the Flying Dakini was conceived.

In India, a pilgrimage to Khajuraho revealed temples enveloped by couples copulating in all conceivable erotic positions, all to illustrate the Power of Sexuality and how it alone can counter Death. In the interior, once all the lust has been drawn out of you, you are faced with a symbol that suddenly erases all that: an abstract erect linggam resting on a circular yoni. “The gods are neither lewd nor prudish. Such notions are human.”

This became an exhibition of low reliefs of the images we saw outside the temples, framed in the romanesque and gothic arches reminiscent of the church windows of my girlhood. They were placed up high, so the viewer looks upward as in prayer.

In Malta we revisited the goddess in her old temples for healing, and went back to a time when people were praying to a mother goddess instead of a god the father.

What do you consider sacred?

Robert Graves’ White Goddess recalls the sound of a hound howling from afar that makes your skin crawl and gives you goosebumps, the Muse from which we draw—inspire—breath, for creating Form out of Vision. Whatever elicits that must be sacred.

The body, as the temple of the Spirit, is sacred too. Its beauty, the undulating mounds and deep valleys, cannot be ignored, must be exalted.