A Century of Posters Protesting Violence Against Black Americans

Designs from a long history of outrage and grief

A phrase I hear a lot these days is that we are living in “unprecedented times.” But when I see images of the protests happening around the world, the only thing unprecedented is the amount of international attention being given to the Civil Rights crisis in America. The messaging on many signs being held up today could literally be from posters of 100 years ago. These are rights that have been repeatedly demanded, grievances that have been exhaustively aired.

While no means complete, what you’re about to read is a brief history of notable posters that have wrestled with and expressed the black experience in America since the turn of the last century. Hopefully it won’t take another century to feel like progress has been made.

On July 28, 1917, over 10,000 African American men, women and children silently marched down New York’s Fifth Avenue to protest the recent murder of black Americans. Men had been lynched in Memphis and Waco in response to the presumed rape and death of two white women, while in East St. Louis at least 40 black citizens were killed in white-led riots related to labor union issues. While not saying a word, these protesters held up posters noting that “Race prejudice is the offspring of ignorance and the mother of lynching.” Despite the huge turnout and notoriety of the march, President Wilson snubbed his meeting with black leaders a few days later and failed to follow through on his campaign promise of outlawing lynching.

The photo by Danny Lyon used as the basis for this poster was taken during a protest led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee against a segregated pool in Cairo, Illinois. On the far left we see a young Congressman John R. Lewis, who at that time was the SNCC Field Secretary before becoming the group’s chair the following year. He has represented the state of Georgia since 1987.

On Aug. 28, 1963, a quarter of a million people arrived in Washington, D.C., from all over America to take part in what would be known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Best remembered as the moment when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, this nonviolent rally asked for the end of discriminatory Jim Crow laws affecting education, employment and housing—all noted in the posters held by participants. This event is considered a watershed moment in the Civil Rights movement, resulting in the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Some of the most impactful organizing for the Black Power movement in the United States occurred during student rallies, lectures and other events. This poster announces a Democratic Society-sponsored talk at U.C. Berkeley in California, featuring a lineup of incredible activists and thinkers. This version of the Black Panther emblem was created by Lisa Lyons.

This poster, clearly riffing on popular imagery of Smokey Bear, was created in the wake of the Watts Riots in 1965 as a criticism of politically moderate African Americans who did not share the outrage of younger generations toward police brutality and systematic oppression. The riots began in response to the arrest of Marquette Fry, a black man on parole for robbery. After Fry was pulled over for reckless driving, the situation escalated quickly, with the police ultimately being accused of kicking a pregnant woman and using unnecessary force to detain Fry. As crowds gathered, the sentiment in the community toward the police boiled over, resulting in six days of civil unrest.

Activist Bayard Rustin had this to say about the events: “The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism, and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.”

This often-misinterpreted poster was created by the Alsatian illustrator Tomi Ungerer. It brutally encapsulates one perspective on global racial struggles—that the constant desire for dominance will end in self-annihilation. Ungerer, self-quoted as being “allergic to war” after surviving the Nazi occupation of France, viewed this image as a cry for peace.

From February to April 1968, hundreds of black citizens marched holding matching posters that read “I Am A Man”—the simplest of statements in response to grossly inadequate safety precautions that had led to the death of two sanitation workers in Memphis. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, the strike intensified. His widow, Coretta Scott King, would join the protests four days later, holding the “Honor King: End Racism” poster. The strike ended the following week, with the city agreeing to union recognition and raises.

OSPAAAL was an international organization that emerged in Cuba under Fidel Castro. It created hundreds of posters in support of oppressed peoples around the world, their sole goal being the decolonization of countries in the post-World War II period. All of their posters feature messages of support in four languages (English, French, Spanish and Arabic). Here are three of many posters they created for the Day of Solidarity with the African American people, held annually on Aug. 19.

No article about the history of black stories in posters would be complete without mentioning the work of Emory Douglas. He created numerous images for the Black Panther Party from 1967 to the early 1980s. He also art directed, designed and illustrated The Black Panther, the organization’s newspaper, which the young boy in this poster is distributing. He is also widely known for his use of strong female figures in his work, which he says were inspired by the many women in leadership positions within the Black Panther party.

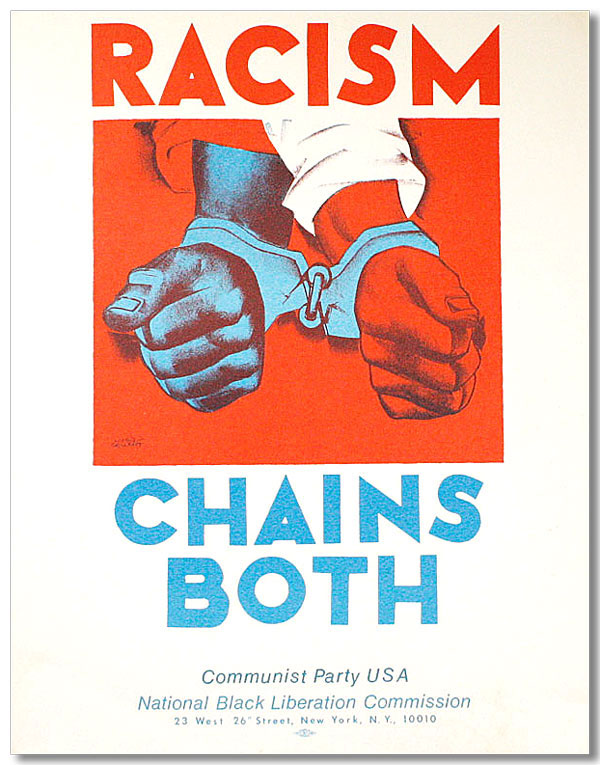

Communist organizations around the world often incorporated imagery of freed Africans in their propaganda. There are, in fact, numerous posters created in China during the ’70s that indicate that Africans will be freed from bondage under Communism. In the United States, the domestic Communist Party and the Black Liberation Commission joined forces to create this poster, noting that what oppresses one of us, oppresses all of us, regardless of political affiliation.

While this image of violence may seem oddly prescient given today’s protests over the murder of George Floyd, it was originally created to honor the death of George Jackson. When Jackson was 18, he was sentenced to “one year to life” for allegedly stealing $70 from a gas station, a charge to which his court-appointed lawyer encouraged him to plead guilty. While in prison, he became a vocal activist for Civil Rights. He was shot and killed by guards in 1971, who claimed he was trying to escape. It was later revealed this was a setup by the police to silence his incendiary rhetoric.

The Black Liberation Army was an underground organization affiliated with the Black Panther Party, active in the U.S. from 1970 to 1981. Their stated goal was to “take up arms for the liberation and self-determination of black people in the United States.” This poster, however, simply calls for the freedom of two of their members, Assata Shakur and Sundiata Acoli, who were convicted of murdering a police officer. While Shakur escaped prison and has lived her life in political asylum in Cuba, Acoli is still serving a life sentence. Behind their figures in this poster we see other figures who fought for black freedom, including Toussaint L’Ouverture, Harriet Tubman, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X and George Jackson.

Issued by the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, this poster was created in response to the violent beating of Rodney Glen King by the Los Angeles Police Department on March 3, 1991. This act of police brutality became a national headline because a bystander, George Holliday, videotaped it from his balcony. Although there was mass public outcry, all the officers involved were acquitted, resulting in six days of rioting in 1992, during which 63 more people were killed. This civil unrest forced President George H.W. Bush to announce that the federal government would charge the officers with violating King’s civil rights. Two of the officers served a prison sentence.

The Black Lives Matter movement was created in 2013 by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who had shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old. Since then, the hashtag has become a universal cry for the basic rights of black people around the world. You need only to look at the content of the protest posters being used today to see that the demands are identical to those being asked for over the past 100 years.