The Greatest Winner: Jordan and the Leadership Dilemma, Part 2

Winning is winning. Unconditionally

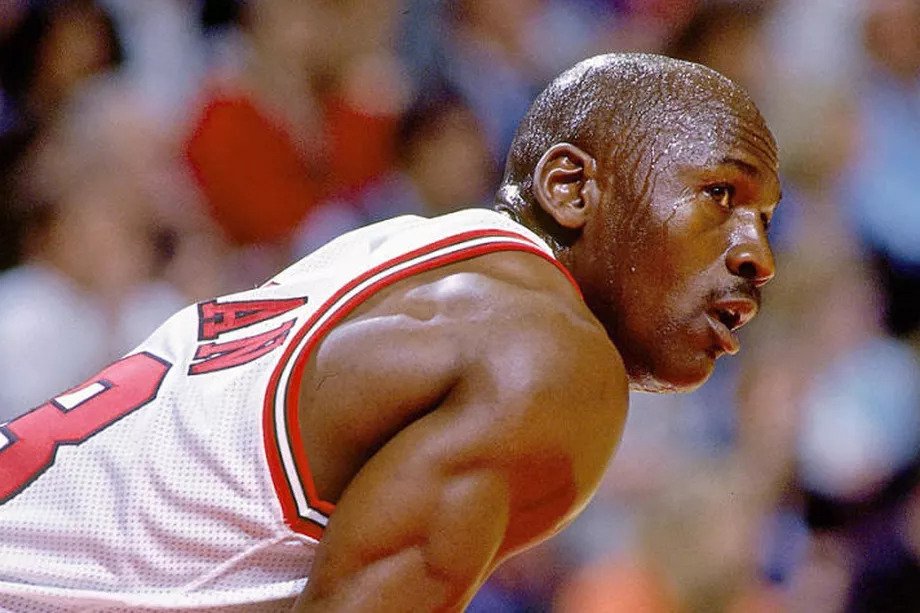

Yesterday I read in this same column an article by Dhaval Bhatt about Michael Jordan that suggested “winning at all costs isn’t really winning.” Well, I wholeheartedly disagree. Allow me to further explore and begin by clarifying that this isn’t, by any means, a jab at my peer Dhaval. Rather, at his take on the magnificent docuseries The Last Dance about Jordan’s unparalleled career and his path to become the greatest sportsperson ever.

I oppose Dhaval’s point of view—which was inspired by his young daughter’s evaluation of Jordan’s antics, condemning his behavior—as I truly believe winning is winning. No matter what. Jordan skyrocketed to superstardom status very early in his career, but still had to prove his worth against the toughest of rivals for seven long years before he even had a taste of the ultimate success: the Larry O’Brien trophy. And only when he accepted that he wouldn’t be enough, that he needed a team to share his victories with, only then did Michael become an NBA champion. And a champion he was for three straight years before an early retirement into baseball.

When he came back to basketball, 18 months later, the winning Bulls team he had help to build had been disbanded, apart from his trusted sidekick Scottie Pippen. Jordan’s determination to win again was resolute. He did not have seven years again to rebuild, reshape, retrain his new team members. He had to adapt his leadership style: harsher, demanding, unforgiving. But not with everybody, though. We all saw how flexible he was with Dennis Rodman, accepting all kinds of outrageous demeanors, thankful to Pippen and appreciative of Steve Kerr (even if they had to lock horns first). Everyone else had to prove themsemselves. If Michael and Phil Jackson (the head coach) felt they weren’t championship ready, then yes, they’d be hard on them. The vision and end goal were the same for everyone, but everyone was on slightly different levels and paths.

Leadership requires adapting to each and every individual in any given team, without ever losing sight of the main goal. Ever. It’s exhausting, no doubt, to constantly being in and out of different stances, shifting gears and hitting the brakes—or the gas, depending on the person—but that’s the cost that must be paid to get to the on top. I believe Jordan deeply cared for his teammates. Sure, he maybe had a strange way of showing it, and maybe even he had his own selfish reasons, but caring is caring. The same way winning is winning.

The most insightful—and emotional—moment of the 10-part series came at the end of Episode 7 in a monologue of Jordan’s that went viral:

“Winning has a price. And leadership has a price. So I pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled. I challenged people when they don’t want to be challenged. And I earned that right because my teammates came after me. They didn’t endure all the things that I endured. Once you join the team, you live at a certain standard that I play the game, and I wasn’t gonna take anything less. Now, if that means I have to go out there and get in you’re ass a little bit, then I did that. You ask all my teammates, the one thing about Michael Jordan was, he never asked me to do something that he didn’t fucking do. When people see this, they’re gonna say, ‘Well, he wasn’t really a nice guy. He may have been a tyrant.’ Well, that’s you, because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win and be a part of that as well. I don’t have to do this. I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that, don’t play that way.”

Don’t get me wrong. I despise bullies. I’m not here to defend Michael. Mostly because I don’t think Michael needs being defended. But I really don’t think he was a bully. Maybe in the eyes of a 9-year-old, sure. But not to a professional who knows when he or she is being pushed around. Twice in my career I had the unfortunate experience of being managed by that type of person. Very early on, when I myself became a creative lead, I decided I’d never go down that path. I can’t even raise my voice to anyone. But I’m OK with that. I can be tough when I have to, but I always, always try to be considerate and constructive in my feedback rounds. And I reckon that empathy is my biggest trait.

Winning occasionally—we can all do it. It happens to everyone. Sometimes even by accident. But winning consistently, year after year, with flair and spectacle, when everybody else is trying to beat you, when your legs, feet, body and mind are not as young as before—that means that the ultimate sacrifice has to come into play: No more Mr. Nice Guy. (Or at least, when it was needed.) And even that was an adaptation. “Adapt to survive. Survive to win” could have been the Chicago Bulls motto during that second three-peat after Jordan’s comeback.

In recent discussions with longtime friends of mine, who all watched Jordan play since the late ’80s, I commented that this type of talent, both the craft on the court and the focused personality, is often a curse. Think of all the greats you know and hold dear. They all manifested an unbalanced life in some way or form. Only a handful of them managed to survive their own greatness. MJ is one of them, maybe fueled by his long list of little personal—and quite amusing, to be honest—grudges. He armored himself with his only weakness—his obsessive, borderline destructive competitive drive—to stay alive and strive to become an NBA champion again, now as an owner of the Charlotte Hornets.

Michael Jordan is part of the most exclusive club ever, that has one member and one member only. Himself. And on that note, I’m fully aligned with Dhaval. MJ is the GOAT, beyond a shadow of doubt. So, if you want to be the greatest at what you do, be like Mike. Adapt, adapt, adapt. Find new ways to win. Or if you want to just be OK, or just occasionally good, take little bits of Mike. Find little reasons to motivate yourself. Anything else are just excuses.

Events

Events